Interview with: Christian Paul Kaeg, CO-Fonder and creative Director of QWSTION

What (on earth) led you to make bags from banana plants?

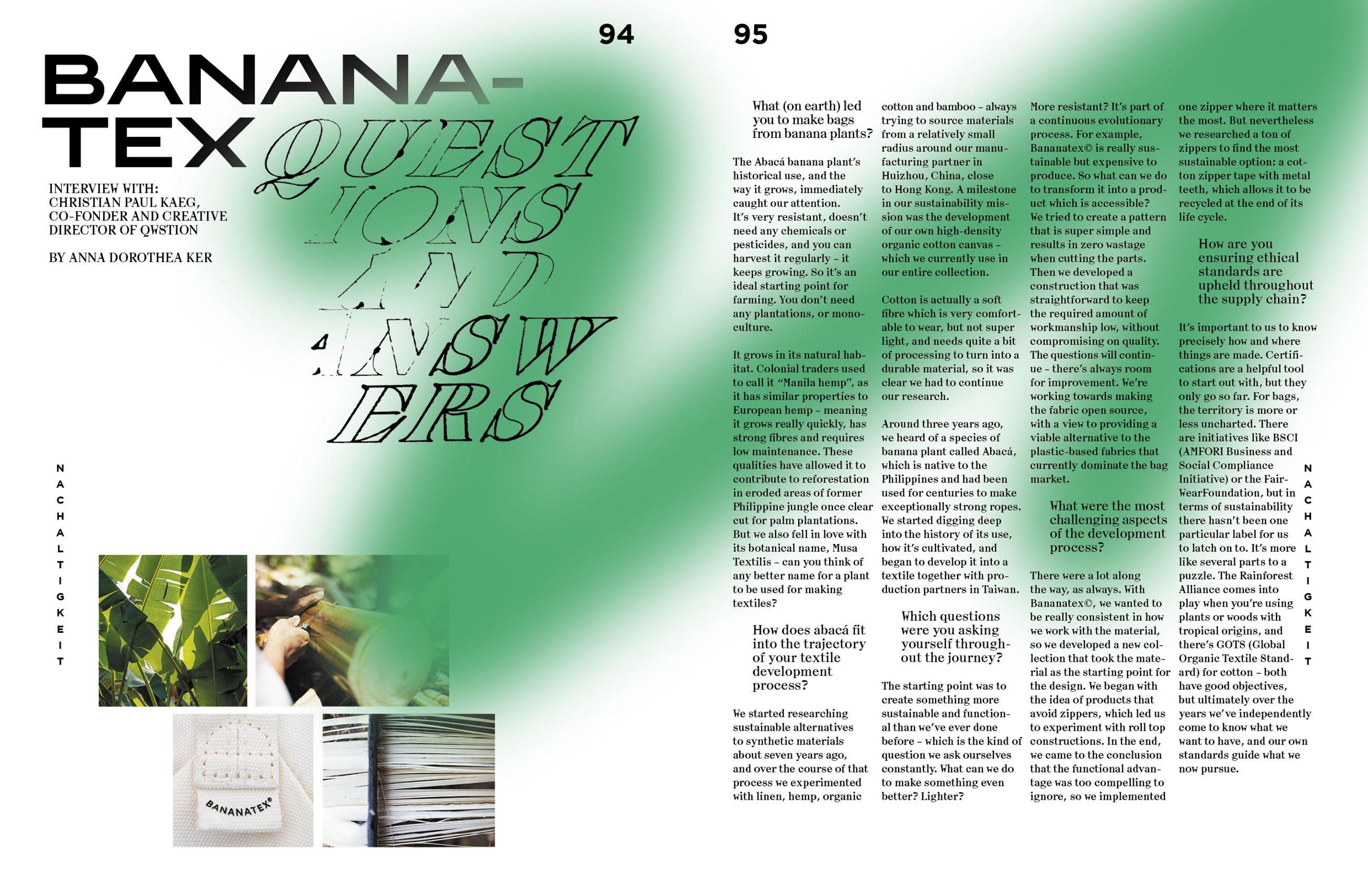

The Abacá banana plant’s historical use, and the way it grows, immediately caught our attention. It’s very resistant, doesn’t need any chemicals or pesticides, and you can harvest it regularly – it keeps growing. So it’s an ideal starting point for farming. You don’t need any plantations, or monoculture.

It grows in its natural habitat. Colonial traders used to call it “Manila hemp”, as it has similar properties to European hemp – meaning it grows really quickly, has strong fibres and requires low maintenance. These qualities have allowed it to contribute to reforestation in eroded areas of former Philippine jungle once clear cut for palm plantations. But we also fell in love with its botanical name, Musa Textilis – can you think of any better name for a plant to be used for making textiles?

How does abacá fit into the trajectory of your textile development process?

We started researching sustainable alternatives to synthetic materials about seven years ago, and over the course of that process we experimented with linen, hemp, organic cotton and bamboo – always trying to source materials from a relatively small radius around our manufacturing partner in Huizhou, China, close to Hong Kong. A milestone in our sustainability mission was the development of our own high-density organic cotton canvas – which we currently use in our entire collection.

Cotton is actually a soft fibre which is very comfortable to wear, but not super light, and needs quite a bit of processing to turn into a durable material, so it was clear we had to continue our research.

Around three years ago, we heard of a species of banana plant called Abacá, which is native to the Philippines and had been used for centuries to make exceptionally strong ropes. We started digging deep into the history of its use, how it’s cultivated, and began to develop it into a textile together with production partners in Taiwan.

Which questions were you asking yourself throughout the journey?

The starting point was to create something more sustainable and functional than we’ve ever done before – which is the kind of question we ask ourselves constantly. What can we do to make something even better? Lighter? More resistant? It’s part of a continuous evolutionary process. For example, Bananatex© is really sustainable but expensive to produce. So what can we do to transform it into a product which is accessible? We tried to create a pattern that is super simple and results in zero wastage when cutting the parts. Then we developed a construction that was straightforward to keep the required amount of workmanship low, without compromising on quality. The questions will continue – there’s always room for improvement. We’re working towards making the fabric open source, with a view to providing a viable alternative to the plastic-based fabrics that currently dominate the bag market.

What were the most challenging aspects of the development process?

There were a lot along the way, as always. With Bananatex©, we wanted to be really consistent in how we work with the material, so we developed a new collection that took the material as the starting point for the design. We began with the idea of products that avoid zippers, which led us to experiment with roll top constructions. In the end, we came to the conclusion that the functional advantage was too compelling to ignore, so we implemented one zipper where it matters the most. But nevertheless we researched a ton of zippers to find the most sustainable option: a cotton zipper tape with metal teeth, which allows it to be recycled at the end of its life cycle.

How are you ensuring ethical standards are upheld throughout the supply chain?

It’s important to us to know precisely how and where things are made. Certifications are a helpful tool to start out with, but they only go so far. For bags, the territory is more or less uncharted. There are initiatives like BSCI (AMFORI Business and Social Compliance Initiative) or the FairWearFoundation, but in terms of sustainability there hasn’t been one particular label for us to latch on to. It’s more like several parts to a puzzle. The Rainforest Alliance comes into play when you’re using plants or woods with tropical origins, and there’s GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard) for cotton – both have good objectives, but ultimately over the years we’ve independently come to know what we want to have, and our own standards guide what we now pursue.